DeFi

Welcome to this week’s Tranched newsletter.

In this week’s edition, we explore the economics of stablecoins, specifically, who captures the yield generated by the reserves that back them.

The recent discussion between Hyperliquid and Circle highlights how different models are emerging. We examine these approaches and what they signal for the future structure of stablecoin markets.

Hyperliquid's decision to launch its own stablecoin, #USDH, after holding more than $5.9B in USDC without access to the reserve yield, has sparked attention. But the bigger story is not about one protocol challenging Circle. It is about the fundamental economics of stablecoins, and how different models allocate the value of the reserves that back them.

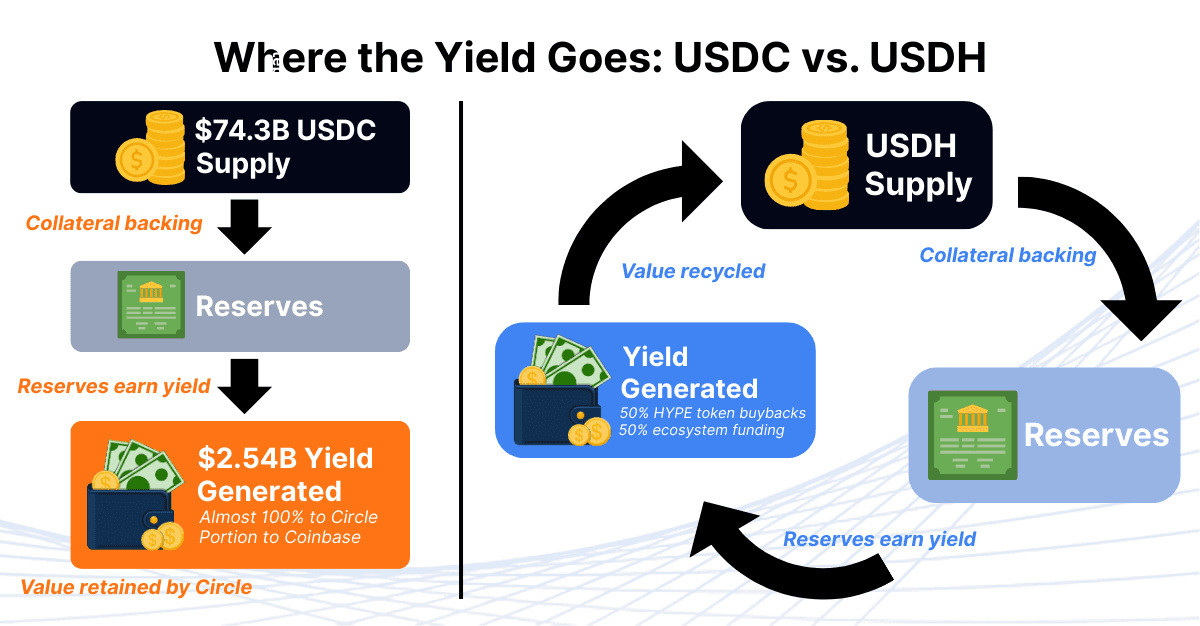

At the core, stablecoins operate on a simple promise: every token is backed by cash or liquid securities. Those reserves are productive, generating yield, largely from short-dated U.S. Treasuries. In USDC’s case, the $74.3B supply translates into $2.54B in 2025 interest income. Today, that yield accrues primarily to Circle (and partially Coinbase through a revenue-share). For users, USDC functions as a utility token: stable, liquid, and widely accepted, but not yield-bearing.

From Circle's perspective, it is a misconception to assume that the stablecoin company intentionally gives nothing back and retains value for themselves. Rather, the reason may be regulatory. If yield were distributed directly to token holders, USDC could fall under securities law in the U.S., drawing SEC oversight and additional compliance requirements. In that sense, Circle’s decision to centralise yield is not only a business choice but also a regulatory safeguard.

Hyperliquid’s move with USDH highlights an alternative. Instead of centralising interest income with the issuer, its model channels reserve returns back into the ecosystem: half to fund development, half to buy back governance tokens. Whether this approach proves sustainable is an open question, but the principle is clear: stablecoin treasuries are being viewed as assets that could finance growth for communities, not only corporate balance sheets.

This approach is not unique to Hyperliquid. Across DeFi and traditional finance, projects are experimenting with different designs:

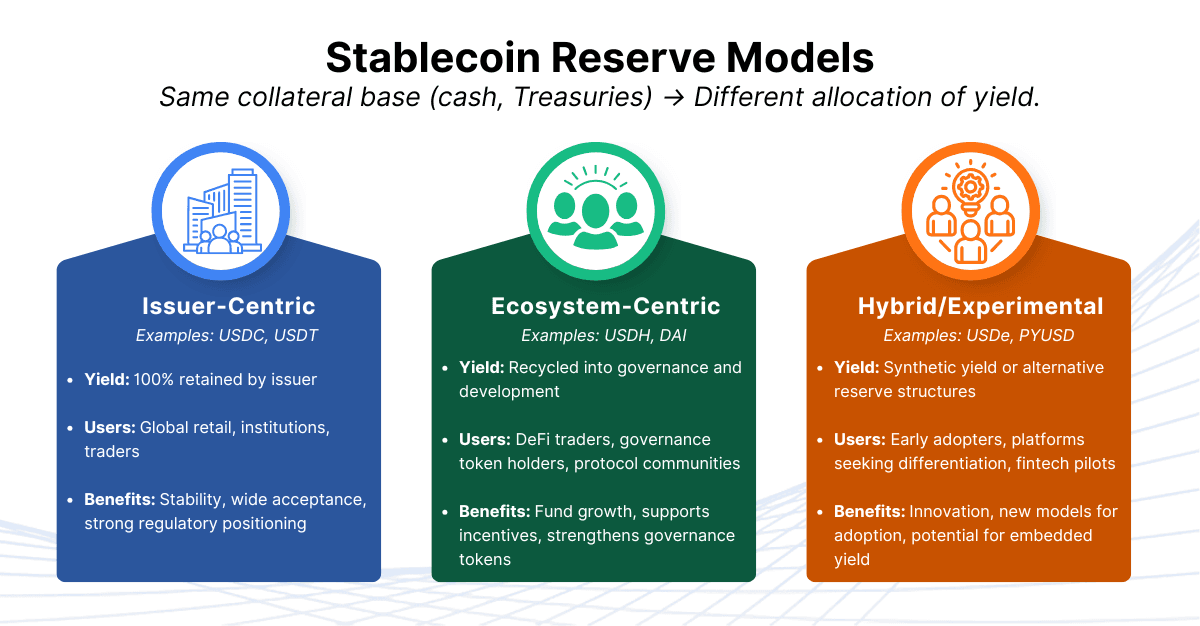

Issuer-centric models (USDC, USDT): yield concentrated at the corporate level, prioritising regulatory caution and balance sheet strength.

Ecosystem-centric models (USDH, DAI): yield channelled into governance, development, or token buybacks to align community incentives.

Hybrid and experimental models (USDe, PYUSD): testing synthetic yield features or alternative structures to differentiate.

Competition is widening. Instead of one or two dominant stablecoins, the market may evolve into a set of issuer-ecosystems, each with its own philosophy about yield, governance, and compliance. This signals broader momentum to move away from custodial stablecoins like USDC and USDT, potentially driving further innovation and competition in the stablecoin market.

As stablecoins mature, reserve economics are becoming as important as collateral quality. For investors and platforms, the choice is no longer just about stability, but also about which economic and governance design they want to align with.

🔵 Should stablecoins be treated more like banks, where depositors share in the yield, or like payment companies, where issuers retain the revenue?

🟠 Will stablecoin markets fragment into multiple issuer-ecosystems, or consolidate around a few players with regulatory approval?

🟢 How should investors think about governance tokens in ecosystems where stablecoin yield is redirected - as equity-like claims, or as experimental mechanisms?