DeFi

Welcome to this week’s Tranched newsletter.

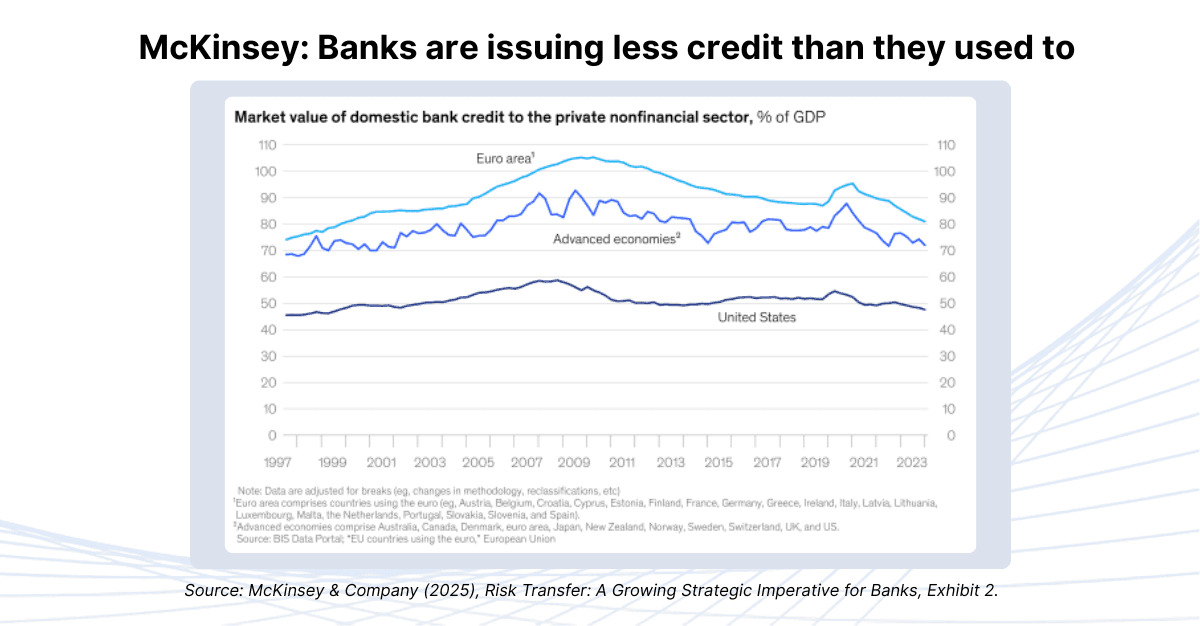

In this edition, we turn the spotlight onto a quietly expanding lever in European bank capital management: on-balance-sheet synthetic securitisation eligible for the EU Securitisation Regulation “STS” label. Its consequences are concrete: it changes how much capital banks can free up, how much risk they transfer, and how much new lending they can originate.

We will address what STS synthetic securitisation is, explain why the boom is accelerating in 2025, explore how it reshapes bank funding and lending capacity, identify the infrastructure frictions beneath the surface, and point to what will determine whether this lever truly delivers.

1. What Synthetic Securitisation Means in the EU Framework

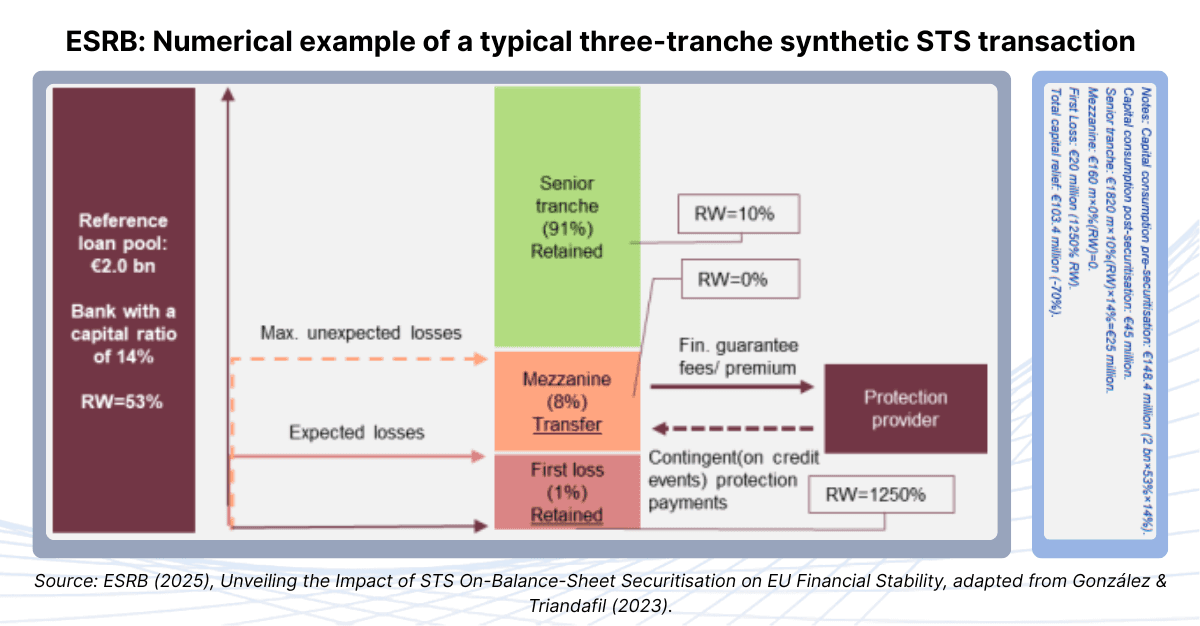

In the EU, securitisation is defined and governed by the Securitisation Regulation (SECR) and the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). Under this regime, synthetic securitisation refers to transactions where a bank transfers credit risk on a defined portfolio of exposures without selling the assets. The loans remain on the bank’s balance sheet, and the risk is transferred through a credit protection contract (typically a financial guarantee or credit derivative) with a protection seller such as an insurer, fund, or another credit institution.

The EU distinguishes between traditional and synthetic structures, but both can fall under the Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS) label. The 2021 CRR amendments extended STS eligibility to on-balance-sheet synthetic securitisations, subject to stringent conditions. To qualify, a synthetic STS transaction must demonstrate:

Transparency: granular disclosure of the reference portfolio and contractual waterfall.

Due diligence: originators must provide loan-level data and reporting consistent with ESMA templates.

Risk retention: originators must keep at least 5% economic exposure.

Significant Risk Transfer (SRT): the bank must prove to supervisors that credit risk has effectively shifted to the protection seller.

Operational requirements: documented criteria for eligibility, triggers, amortisation, and servicer continuity.

In practical terms: synthetic STS securitisation frees regulatory capital, but does not generate funding, as the assets never leave the balance sheet.

The Synthetic Securitisation Landscape in Europe

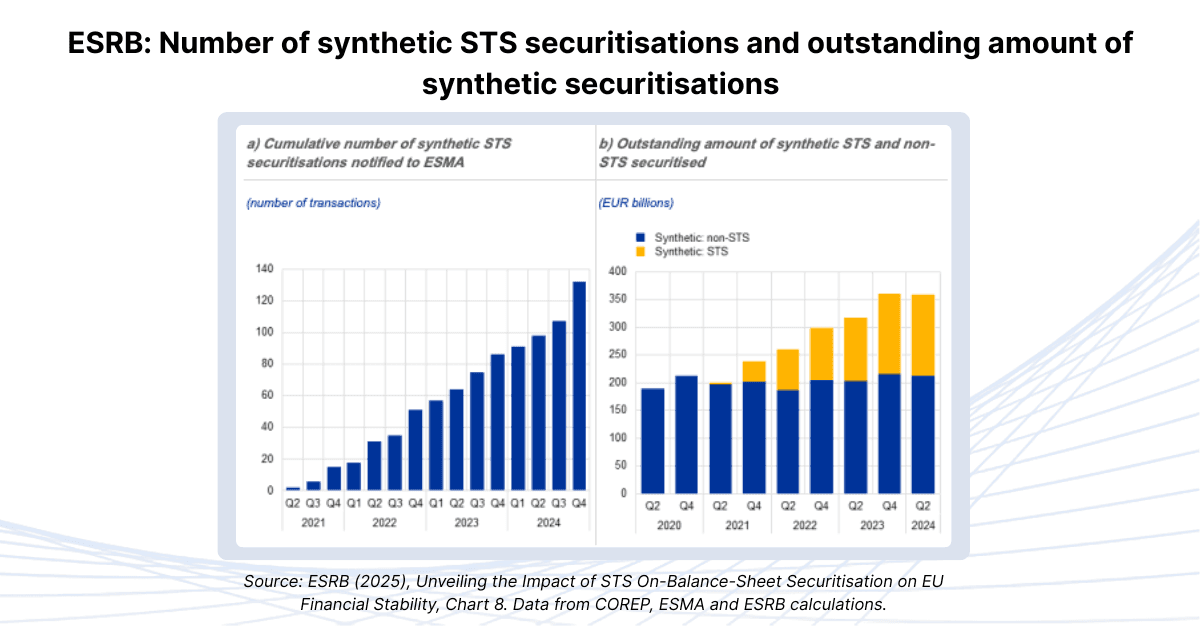

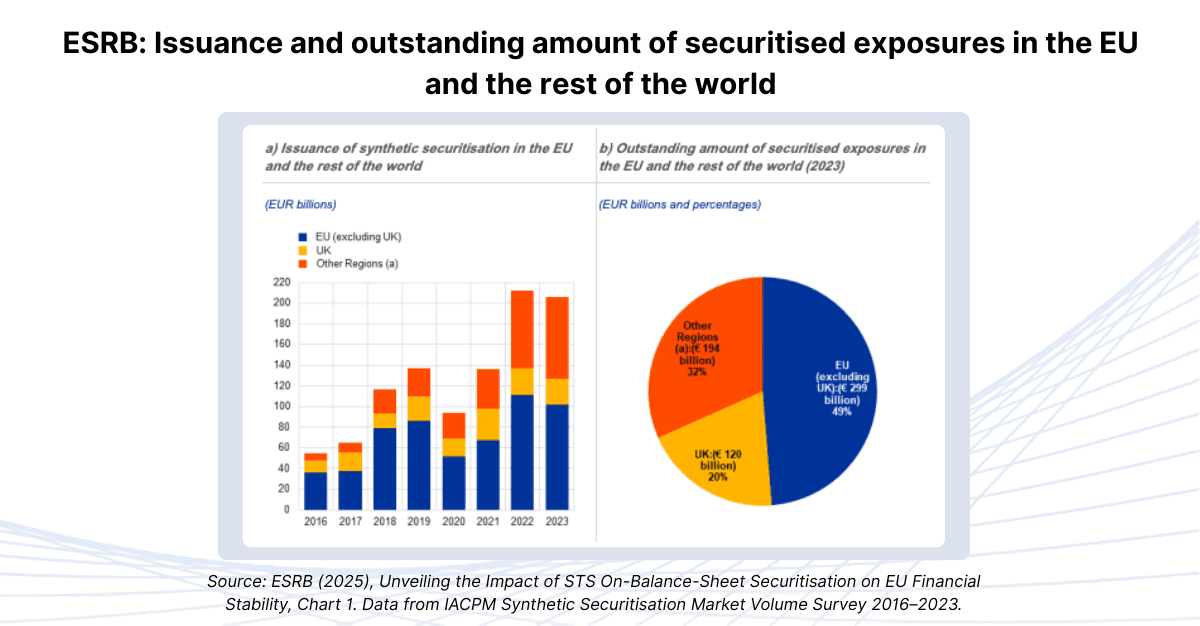

Synthetic securitisation has become the most dynamic part of Europe’s securitisation market, expanding while traditional issuance remains subdued. Since synthetic deals became eligible for the STS label in 2021, activity has accelerated sharply. By 2023, euro-area synthetic issuance had reached roughly €140B, nearly doubling 2021 volumes and outpacing every other segment of structured credit.

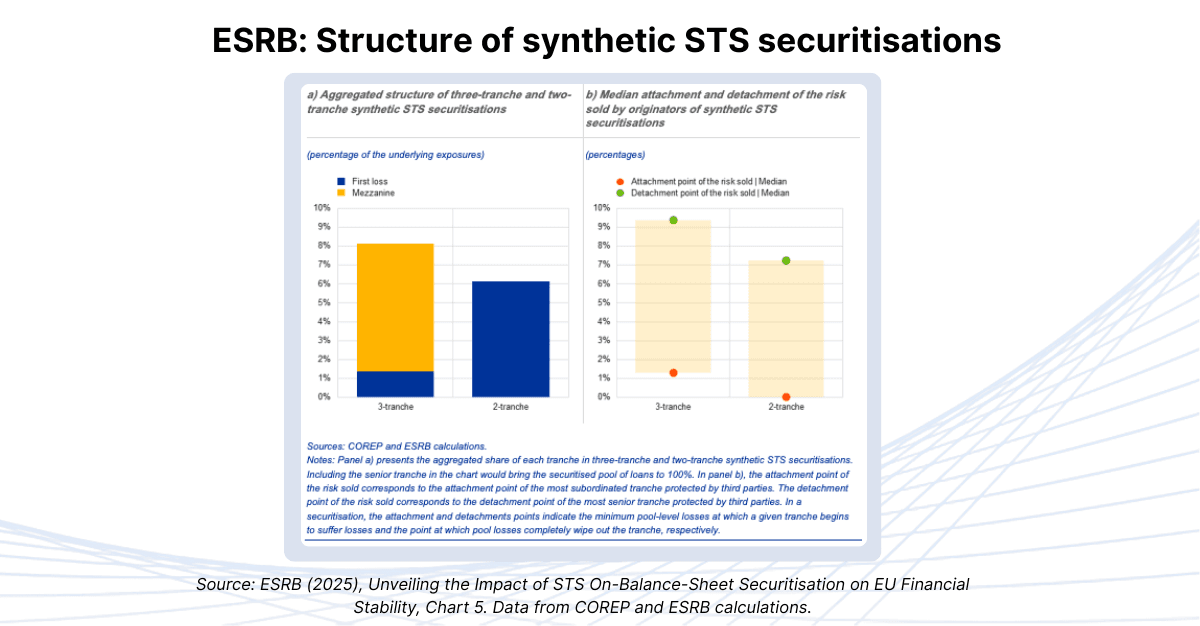

The STS segment itself has scaled at remarkable speed. Outstanding STS synthetic exposures grew from zero in 2021 to €145B by Q2 2024, now representing around 40% of all synthetic securitisations in the EU. Deal sizes are larger, structures are more standardised, and the volume of notified STS transactions (98 deals by mid-2024) shows that synthetic STS has moved from marginal to mainstream.

This growth is highly concentrated among Europe’s largest banks, which account for more than 50% of all outstanding STS synthetic exposures. Yet even for these institutions, the reference portfolios remain small relative to total assets (around 1% on average). This reinforces an important point: synthetic securitisation is not reshaping bank balance sheets, rather it is being used as a capital-management tool, to optimise RWA rather than transfer assets.

The composition of underlying assets also distinguishes synthetic securitisation from the traditional market. Whereas cash securitisation in Europe remains dominated by mortgage assets, around 80% of synthetic transactions reference corporate and SME loans. This shift matters because it ties synthetic securitisation more closely to real-economy credit, and makes its capital-relief effects more directly relevant to business lending.

The next set of risks comes from who absorbs the risk and how these structures behave under stress. Risk transfer is increasingly cross-border and non-bank led, with around 75% of funded protection sellers based outside the euro area, primarily in the US and UK. Within the EU, the dominant investors are open-ended investment funds, raising questions about liquidity management and maturity alignment. This shifting investor mix materially deepens interconnectedness between banks and non-bank financial institutions.

At the same time, the ESRB emphasises that synthetic STS structures have never been tested through a full credit cycle.With low attachment points and short maturities of around three years, these deals carry clear procyclicality and rollover risks: losses can produce sharp RWA increases at the wrong moment, and protection sellers may hesitate to renew precisely when banks most need capital relief.

Taken together, these trends show a market that is scaling rapidly, becoming more systemically relevant, and reshaping how credit risk moves through the European financial system, but one that now requires infrastructure capable of supporting this growth with accuracy, synchronisation, and real-time verification.

Why the Boom Is Happening in 2025

Several forces combine to drive the rising use of STS synthetic securitisation:

1. Regulatory design now materially improves capital relief The EU’s decision to extend the STS label to synthetic transactions (2021) changed the economics of risk transfer. STS eligibility lowers the risk-weight floor on senior retained tranches from 15% to 10%, and halves the p-factor surcharge under the standardised approach, which significantly increases the capital benefit delivered by mezzanine protection.

Combined with Basel IV output floors and constraints on internal model usage, banks increasingly turn to synthetic SRT as a precise alternative to equity issuance for CET1 optimisation.

2. Supervisors and policymakers are explicitly signalling “more securitisation” The ECB has made it clear that a larger securitisation market would “invigorate and deepen” European capital markets and support economic financing.

At the same time, the European Commission’s 2024 consultation and the 2025 reform package propose simplified due diligence, more favourable capital treatment and targeted adjustments to spur issuance, positioning securitisation as part of the EU’s competitiveness and Savings & Investment Union strategy.

The message is clear: STS activity is aligned with EU policy goals, reducing political and supervisory friction.

3. Non-bank capital is expanding and actively searching for bank credit exposure Private credit and other non-bank investors have grown assets under management by ~11% per year, and more than $1.1T in underlying assets has now been covered by synthetic securitisations globally, with Europe representing roughly two-thirds of issuance.

IACPM survey data show 500+ SRT transactions between 2016–2023, covering more than €1T of loans and €80B of first-loss and mezzanine tranches.

This is the ideal risk–return product for institutional investors: diversified exposure, predictable maturity, and structured protection.

Structural weaknesses that will slow scaling

Synthetic STS growth is concentrated in a handful of large banks and depends heavily on cross-border, non-bank protection sellers. This creates a simple challenge: a rapidly expanding, largely bilateral market is now operating on infrastructure built for a slower, more static securitisation era.

Data and documentation are therefore a first fault line. Synthetic risk transfer depends on the accuracy of reference portfolios, modelled loss assumptions and contractual protections. The IMF’s October 2024 Global Financial Stability Report explicitly warns that some features of synthetic risk transfers “may warrant close supervisory monitoring” due to opacity and the potential for negative feedback loops between banks and non-bank investors.

Timing is the second issue. Many structures rely on monthly or quarterly tests of eligibility, performance and significant risk transfer, even though credit risk on granular portfolios can migrate much faster. IACPM survey data indicate that protected tranches often sit at very low attachment points – in many cases between 0% and around 8% of the portfolio – so modest increases in default rates can quickly erode protection and push losses up the capital structure. In a downturn, that combination of thin mezzanine protection and slow-moving triggers risks turning capital relief into procyclical capital consumption as RWAs jump on the remaining tranches just as banks’ earnings deteriorate.

The third challenge is infrastructure. Most of the legacy machinery for securitisation reporting was built for public, cash deals with SPVs and prospectuses. Synthetic transactions, by contrast, are often private placements, reported to national supervisors rather than central repositories and structured through credit-linked notes or guarantees. ESRB data confirm that synthetic securitisations are predominantly private and tailored to specific investors’ risk–return preferences.

Without a synchronised asset registry and automated covenant logic, verification of risk transfer remains reliant on static loan tapes, bilateral documentation and manual reconciliations – a poor fit for a market that is now handling portfolios in the billions.

Finally, the risk is not confined to individual banks. ESRB statistics show that investment funds and pension funds are the main protection sellers for synthetic STS, with a significant share outside the euro area.

IMF work on synthetic risk transfers and broader non-bank exposures highlights how these links can amplify stress if investors face redemptions or liquidity shocks, especially when exposures are funded with short-term liabilities or embedded in open-ended funds. The danger is a loop in which banks transfer risk to non-banks, lend to those same non-banks or rely on them for funding, and then find the risk re-entering the system through different channels when markets turn.

Against that backdrop, the trade-off is clear. Synthetic STS offers genuine capital benefits and portfolio flexibility, but the current infrastructure and disclosure regime were not designed for a world where these structures are large, frequent and systemically relevant.

The Journey Ahead: Why the Next Phase Depends on Infrastructure Built for Speed and Accuracy

The expansion of synthetic STS securitisation brings clear benefits, but it also exposes a structural truth: today’s systems were built for periodic, document-driven reporting, not for continuous, synchronised verification across banks and non-bank investors. Better data, more automation and stronger governance are prerequisites if risk transfer is to scale safely.

A modern framework therefore needs three capabilities.

First, real-time or near-real-time validation of risk transfer, so that changes in portfolio composition, credit performance or protection coverage are reflected quickly in both supervisory metrics and investor dashboards.

Second, a tamper-evident, shared registry of reference assets and tranches, giving originators, protection sellers, investors and supervisors a common view of exposures and their lineage.

Third, automated control mechanisms that run at transaction speed, recalculating triggers, concentration limits and capital metrics on live data rather than month-old tapes.

These are not abstract aspirations. Banks are already assembling richer data resources, deploying more granular analytics and simulating portfolio behaviour under alternative risk transfer strategies to support internal decision-making and SRT approvals.

The next step is to embed those capabilities in market infrastructure that can serve multiple counterparties at once.

If that happens, supervisors will be better equipped to monitor protection-seller concentrations and reinvestment loops; non-bank investors will have clearer, more standardised information; and policymakers will be able to test whether capital freed by synthetic STS is genuinely flowing into new lending.

Without it, the market will continue to grow on foundations that were never designed for its current speed or complexity.

The opportunity now is to build securitisation on rails capable of continuous assurance, so that the quiet boom in synthetic STS strengthens the system rather than stretching it.